A Brief Introduction to Chinese Art

By Jason Sun

|

Terra Cotta Warriors in the tomb of the First Emperor, Qin dynasty

(3rd century B.C.) |

|

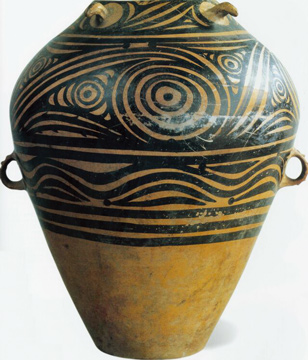

Chinese art is as old as Chinese civilization, which traces its beginnings to the late Neolithic period some 7,000 years ago. Most remarkable among the Neolithic arts are the pottery vessels with painted decoration created by the inhabitants in the Yellow River valley. Made of finely prepared clay, the vessels have relatively simple but well-proportioned shapes. On their smooth, buff surfaces are abstract patterns executed in black pigment. While these vessels share certain forms and decorative patterns with cultures elsewhere in the world, they exhibit a peculiar Chinese trait: fluent, rhythmic lines drawn with a brush, an essential feature of much of later Chinese art.

Equally remarkable are the carved jades from the prehistoric cultures on China's eastern coast. The jades generally fall into two categories: personal ornaments and ritual objects. They are known for their delicate details and lustrous finish. The possession of jades must have been a privilege of the social elite, because the material, nephrite, is both extremely rare and extraordinarily hard, so its working involves great skill and a tremendous investment of labor. With all its desirable qualities, such as color, translucency, hardness, and a sensuous tactile feel, jade has become associated with spiritual power and virtuous behavior. It has remained the most precious and prestigious substance in the history of China.

|

| Neolithic period Jar, Majiayao culture (3300-2050 B.C.), Earthen-ware with painted decoration |

|

China’s Bronze Age began in the second millennium B.C.E. Although its origin still remains unclear, China’s bronze casting technology appears to have been a largely independent development and had become quite advanced by the middle of the millennium. In contrast to the smithing and lost-wax processes of the West, early Chinese bronze workers employed the ceramic section-mold method, by which movable clay sections are assembled around a clay core to form the mold. This not only enabled the casters to control the shape of the bronze to be cast, but also offered them full access to the inside of the mold, thus allowing them to produce bronzes with relatively simple, symmetrical shapes but extremely complex surface d6cor. Bronzes were not made for pure aesthetic appreciation but for such practical functions as weaponry or food and wine containers to hold offerings in religious rituals. Their forms and decorations, featuring fantastic animal masks, were meant to inspire reverence and awe. China's Bronze Age ended with the fall of the Eastern Zhou dynasty in the 3rd century B.C., when sumptuous lacquer vessels began to replace bronzes and the pursuit of worldly pleasures led to the production of luxurious textiles and exquisite jades.

With the fall of the Eastern Zhou, the Qin dynasty arose, which had defeated all the other regional states and established the first Chinese empire. Although Qin was short-lived, lasting for less than two decades, it left an imposing legacy. The bureaucratic administrative system it created became the mode of rule and the Great Wall it built remained an effective defensive bulwark for centuries to come. One of the most spectacular of its accomplishments was an enormous terra-cotta army, which archaeologists found in the burial ground of the first Qin emperor. The army comprises thousands of life-size pottery figures of soldiers, officers, archers, and charioteers arrayed in battle formation. The figures, among the earliest life-size human representations in Chinese history, were made of molded parts, their painstakingly finished heads displaying diverse face types and and hairstyles. They were originally painted with bright colors, which unfortunately have largely been lost since the burial pits were uncovered. The making of the terra-cotta army is tribute to Qin art as well as to its social organization and ability to mobilize an extraordinarily large labor force.

|

Ritual Food Vessel (ding), Western Zhou dynasty (1046-771 B.C.)

Bronze |

|

The Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220 C.E.), which replaced the Qin ruled for over four hundred years. While little has survived above ground, archaeologically recovered pottery figures offer a fascinating view of the life and material culture of the time. Figures of musicians, dancers, and game-players portray activities of the elite, while architectural models of houses, kitchens, wells, granaries, animal-pens, and even multi-storied watchtowers with archers, illustrate life in farming villages and on large estates. With its powerful military, the Han dynasty greatly expanded its territory by bringing under its control not only neighboring states in the north and south but also more distant regions in the far northwest. This tremendously facilitated the traffic over the Silk Road, the renowned trade route that linked China with Central and Western Asia and Europe, resulting in an unprecedented influx of foreign products, arts, ideas, and religious practices. The colossal stone sculptures of lions and winged mythical animals that stood at the entrances to imperial palaces and tombs are imposing manifestations of West Asian influence. But China’s contact with the outer world began long before this. As early as the early first millennium B.C. the nomads of the steppes had already introduced animal motifs and metalworking techniques. More striking are the fragments of a few pottery human figures recently found at the burial site of the Qin emperor that bear unmistakable characteristics of Hellenistic sculpture.

|

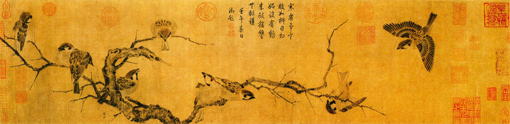

| Sparrows in Winter, Cui Bai (late 11th century), Northern Song dynasty (960-1125), Ink and color on silk |

|

After the Han dynasty collapsed in the early third century, its empire dissolved into a succession of regional states. For the next three and a half centuries, the incessant warfare among these contending powers constantly disrupted the social order. Paradoxically, this chaotic period was also a time when China experienced a massive influx of foreign ideas, customs and material culture. Buddhism entered China from India and Central Asia, and, with it, a religious sculpture that reached a high pitch of excellence in the sixth century. The slender, graceful Buddhist figures, with their rhythmic flow of drapery, have a special charm. They must have been a source of solace for those who sought help and blessing during this time of suffering and unrest. Also from the West came textiles and metalwork that spurred new decorative motifs and a radical change of color schemes.

|

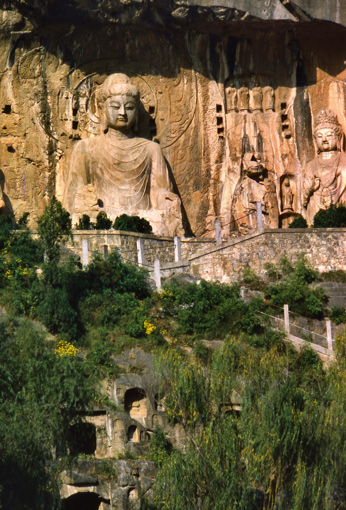

| Longmen Cave, Tang dynasty (618-907), Longmen, Henan province |

|

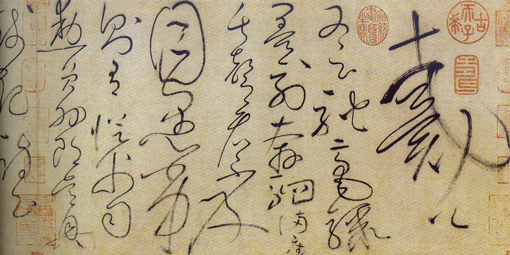

The Tang dynasty (618-907) reunified the country and ushered in a golden age in the arts. Vitality and strength are the character of Tang art, which is most apparent in the Buddhist sculptures of the Longmen Cave temples. The giant Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and guardian gods exhibit a remarkable fullness of the human figure and dramatic force of its postures. The dynamism of Tang art is also seen in metalwork, jades, textiles, and ceramics. Realistic pottery tomb figures, for example, are animated by vigorous lines and vibrant colors. Calligraphy was the most acclaimed art form of the time, with great masters such as Ouyang Xun and Yan Zhenqing setting the standard for generations to come. Tang regular script, now fully matured, integrated supple, modulated brushwork with a balanced structure.

The fall of the Tang saw the rise of three contending powers. The native Song dynasty (960-1279) controlled much of the Chinese heartland while two non-Chinese dynasties, the Tangut Liao (907-1125) and the Jurchen Jin (1115-1234) succeeded one another in the north. During the Song dynasty painting was the most celebrated art. Artists in the imperial academy were encouraged to take Nature as their model but also imbue their images with a poetic touch. The landscapes, figures, birds-and-flowers, and urban scenes that they created capture the minute details of life yet also convey a sense of elegance. Song ceramics constitute the highest achievement of the Chinese potter. The porcelain wares with unctuous, high-fired glazes display a wide range of tasteful colors, including white, ivory, subtle green, pale blue, purple, brown and black. Their simple and refined shapes are no longer derived from metalwork models but epitomize the aesthetic of pure ceramic forms. The art of the Liao and the Jin dynasties, on the other hand, carried on Tang traditions as exemplified by spirited dragons and phoenixes on their textiles and metalwork.

|

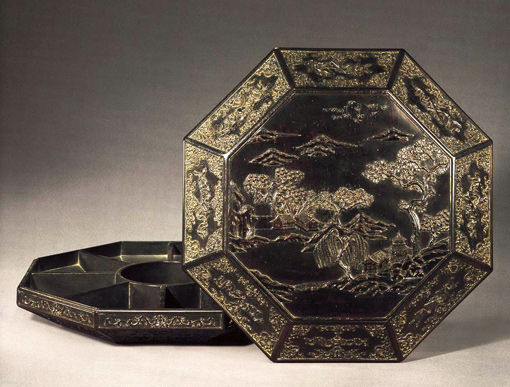

| Box, Ming dynasty (1368-1644), Lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay |

|

In the brief Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), when the great Mongol empire dominated much of the Eurasian continent, China renewed its contact with the West. Chief among the foreign influences of this time are the arts of Islamic West Asia and of Nepal and Tibet. The impact of the former is evident in the floral motifs on porcelain and textiles; that of the latter is most apparent on Buddhist painting and sculpture. As many educated Chinese refused to serve in the Mongol government, they took refuge in the pursuit of art, which led to a flourishing of literati painting, or the painting of amateurs. These scholarly artists abandoned the formal conventions of the past and emphasized self-expression. The foremost literati master was Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), who painted bamboo, rocks, and landscapes with powerful calligraphic brushwork. A versatile artist, Zhao also practiced and passed on the old tradition of figures and landscapes with descriptive lines and brilliant colors. He is most renowned for his beautiful, elegant, and sophisticated calligraphy, which became the model for contemporary and later typefaces used in printing.

The native Ming dynasty (1368-1644), which succeeded in driving the Mongols beyond the Great Wall, dedicated itself to restoring the former glories of Song art. The official kilns produced porcelain of great delicacy and refinement. The decoration, painted in underglaze blue or red, comprises an astonishingly large variety of motifs, such as animals, figures, floral designs, and narrative illustrations, which were made readily available by the mass-produced woodblock prints. The Ming court also patronized many other forms of decorative art, including textiles, metalwork, and particularly carved lacquer. Popular decorative themes on carved lacquer include figures in complex architectural and landscape settings and elaborate floral patterns. Lacquer wares inlayed with mother-of-pearl were also highly developed in the Ming. The iridescent luster created by thin cutouts of mother-of-pearl enhanced the wares with a sumptuous appearance.

|

|

| Vase with Phoenix and Flowers, Qing dynasty (1644-1911) or later, Jade (nephrite) |

Vase, Qing dynasty (1644-1911) or later, Porcelain with overglaze enamel colors |

|

The art of the Qing (1644-1911), the last dynasty in Chinese history, is distinguished by the refinement of materials and perfection of techniques. Carvings of jade, ivory, lacquer, and wood are admired for their intricate shapes, exquisite details, and impeccable craftsmanship. Textiles and metalwork, too, display ingenious designs and uncanny skills. The chief contribution of the Qing to Chinese art is in ceramics. The palette of monochrome glaze porcelain was enriched with numerous delightful colors, including “ox-blood” red, “peach-bloom” red, mustard yellow, apple green, tea-dust green, powder blue, sapphire blue, and pale “clair de lune”blue. Another novel development was the decoration on plain white porcelain with the opaque enamel colors, in which the newly introduced pink and carmine play the title roles. Some of the decorations, painted by talented court artists, are among the most outstanding works of the time.

|

| Autobiographical Essay, Huaisu (ca. 735-799), Tang dynasty (618-907), Handscroll, Ink on paper |

|

Chinese art entered its modern era in the twentieth century. The opening of China to trade and diplomacy put Chinese artists in direct contact with the outer world. Many painters began to learn from and experiment with Western ideas and artistic practices. Their dynamic interaction with Western modes of painting has produced a rich and diverse range of modern Chinese art. Some have created eclectic styles that combine East and West, while others explored the inexhaustible store of traditional formats and motifs, reinterpreting them in the language of modern art. This process of innovation and revival has just begun, however, as Chinese artists continue to search for effective means to express their thoughts and emotions. More splendor and excitement have yet to come.

Jason Sun, Curator, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. He has lectured and published widely on his area of expertise including jade carving, metalwork, calligraphy, and Chinese archaeology. Among his publications are contributions to Providing for the After Life, Ancient Chinese Art from Shandong (2005), China: Dawn of a Golden Age (2004), The Golden Age of Chinese Archeology (1999), The Art and Culture of Chinese Calligraphy: Selections from the John B. Elliott Collection (1999), Chinese Jades: Colloquies on Art and Archaeology in Asia (1997). |

|